Written by Lauren Chin

We have great news! A wonderful study about equity and inclusion in the classroom recently came out, and one of our volunteers, Lauren Chin, broke it down for us below! Based off of the study Toward Inclusive STEM Classrooms: What Personal Role Do Faculty Play?, we are excited to share some insights on creating an inclusive classroom.

Say this sentence out loud: “I love to read, and I am great at understanding both science and social science.” Okay, continue on, we’ll come back to this later....

If you are reading this article, you likely attended school in a classroom at some point in your life; do you remember anything about a specific instructor or the assignments they gave that made you either love or hate going to school or completing classwork? The fact that you remember these experiences weeks, years, and maybe even decades later shows you the impact that an educator can have on your academic life. As scientist-educators, we can all use the privilege of teaching the STEM leaders of tomorrow to harness a love of learning and curiosity, diversity, inclusion, and equity in these bright minds. We all love collecting and analyzing STEM data, but looking beyond our STEM box to our social science colleagues may help us in addressing our own obstacles to inclusion. A few years ago, two female science professors from Massachusetts shared their pedagogy (methods or practices of teaching) rooted in other educational, psychological, and sociological studies about how we can shape our teaching to achieve our goals of not just diversity, but of inclusive diversity in STEM classrooms.

Privilege and Belonging

Well-intentioned teachers may conduct their classroom activities in a way they think is helpful to their students’ learning, e.g. having students write out examples of nouns and verbs on paper, but which in practice may hinder the learning of students who have different backgrounds, interests, or resources to the instructor, e.g. students who are English learners and would gain more meaning and context from speaking these parts of speech aloud with peers. Again, actions such as these may be inadvertent, but taking the time to reflect on our privileges (parts of our identities that give us unintentional advantages and make it easier to both find successes and feel a sense of belonging in a particular social system) will be valuable to us and our students. Since privileges are so closely linked to our identities, they influence our educational paths and life experiences in distinct ways from those who do not share the same set of privileges. Students may also be members of multiple groups that each lack their own privileges; addressing such intersectionality highlights the overlapping and synergistic marginalized identities of individuals such as Black girls, gender-nonconforming Asian American children, or indigenous children with learning disabilities, and can help us adapt our classrooms for everyone’s success.

A sense of belonging also plays a large role in students’ academic and professional STEM careers (see our previous blog post here) that continues into graduate school and beyond. Even today in Boundless Brilliance’s Draw-A-Scientist exercise, we see a majority of pictorial men in lab coats, similar to the results of a study from 1983, which means many students at a young age may not envision someone like themselves becoming a scientist. Couple together the lack of privileges and resources with a lack of representation or mentorship, and underrepresented students in STEM may be discouraged and leave the field. Therefore, we are hard-pressed to create an inviting classroom environment that not only acknowledges our students’ diverse traits, but adapts to our students and invigorates their learning as well.

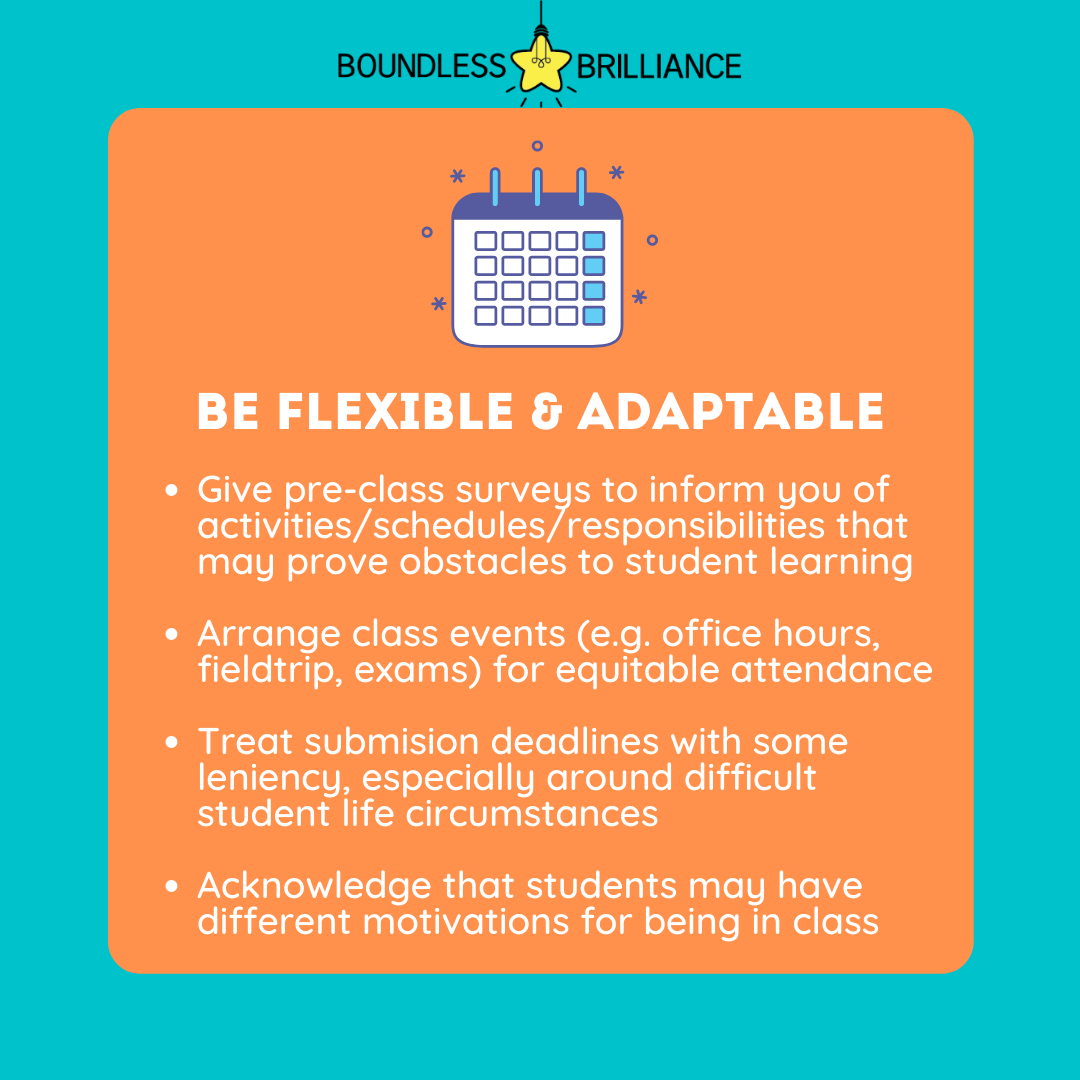

To address these challenges in the classroom, we can pursue a variety of options:

Introduce yourself at the beginning of a course and incorporate non-academic aspects of your identity

Be flexible and adaptable when it comes to submission deadlines and sudden difficulties

Highlight the contributions of scientists from underrepresented groups in STEM

Interact with student groups outside of the classroom

Give students choices in assignments so that they can address their interests

Younger Classrooms:

Give students and/or their families surveys at the beginning of each school year to inform you of activities/schedules/responsibilities that may prove to be obstacles to learning

Older Classrooms:

Acknowledge that students may have different motivations for taking the course

Give students pre-course surveys and use the results to shape course aspects equitably

Direct students to appropriate resources

Reflecting on my experiences as an educator of collegiate students, I realize that my TA, in introducing herself as a plant and dog lover with a mirror selfie, made herself more approachable at the start of the course as compared to my own introduction solely centered around my academic, scientific interests. However, I did make my classroom environment more inviting and engaging by asking students one-on-one why they were taking the course, the best time for office hours, what they wanted to learn, and what hobbies they had, to draw upon in my future lectures and class discussions. In terms of being flexible, if learning in a pandemic is a difficulty, imagine the unexpected death of a loved one; give the student grace and time. When this occurred in my course, I not only allowed the student to turn in assignments at their own pace until grades were due, but I also researched school resources that would assist them in the circumstances.

Implicit Biases

Quick! Think of a scientist! Chances are you thought of a white male. But I actually thought of Mae Jemison and Tu Youyou, I swear! While that may be true for you as well, I bet for a split second even before your brain comprehended the task that you saw a glimpse of Albert Einstein in your mind as your eyes landed on the word “scientist.” It’s okay, I did too. Admitting that we have ingrained ideas from our childhood and life experiences is just the first step in addressing implicit biases. An implicit bias is an automatic cognitive association that is activated in response to a stimulus (e.g. a cultural first name) with a strong stereotype. Just as the name suggests, it is unconscious and hard to control, so don’t beat yourself up when the image of a woman in a t-shirt on a boat doesn’t instantly pop up when you hear “scientist.” However, these biases can still influence our thoughts and actions even when they conflict with our conscious personal beliefs and values surrounding race, sexuality, gender, disability, etc. Essentially, to prevent implicit biases from disrupting our classrooms and lives, we have to either rewire our brains (a severe challenge, but doable over time) or conduct our classroom in a bias-independent way (much easier and faster). For the latter:

Actions Against Implicit Bias

1) Recognize our implicit biases. Try taking a few Implicit Association Tests (IATS).

2) Reflect on how this may affect our interactions in education as students and educators.

3) Cognitively/consciously negate stereotypes and affirm counter-stereotypes (as opposed to assuming that we can suppress implicitly biased thoughts unconsciously and proceed as usual, which is actually counterproductive).

4) Use concrete strategies to address our biases in the classroom:

Pause and consider if stereotypes are at play in your lesson plan

Remove identifying information from student work before grading

Use pre-designed rubrics for assignments or applications to leave no room for bias, unconscious or otherwise

The IATs are by no means fully diagnostic tools, but they are helpful in your reflection process! They were very easy and quick to take, <5 minutes each! My result specifically for the Asian and European Americans IAT below consisted of only 2% of test-takers, but realizing I was born and raised in an ethnoburb in the U.S. with a predominantly Asian American population where only a few white teachers composed my interactions with white Americans, this now makes sense. However, I do now realize that my interactions with white peers in college may have been slightly awkward in my mind since I unconsciously distanced my culture and experiences from theirs, despite most of my peers being fellow Americans and Californians. With these new considerations in mind, I now consciously approach my interactions with others from different backgrounds with the positive intent to know them better and find common ground. In regards to my gender and academics IAT, I believe that this stems from my interactions with most of the girls I knew at my high school pursuing science, most of the boys I knew at my college pursuing non-STEM degrees, and most of my family’s medical doctors being women, which goes to show how important representation in a child’s life is!

Stereotype Threat

Individuals experience stereotype threat when performing a difficult task that members of their group are thought to stereotypically do poorly at; it is much like a self-fulfilling prophecy. This especially applies to underrepresented students in STEM courses for which the additional pressure to succeed leads to cognitive and physiological stress, taking up their mental and emotional resources and leaving less resources available to think logically. In contrast, removing this extra pressure gives these groups of students the opportunity to meet their fullest potential in the classroom. While we may not be outright declaring stereotypes before administering an exam, something as seemingly innocuous as saying, “Good luck girls and boys,” as opposed to “Good luck to all of you,” may make girls more self-aware of their female identity and lead to underperformance.

Similarly, introducing students to assignments or exams as “diagnostic” may unconsciously cause students to take the experience and/or results as a measure of intelligence or ability. Thus, fostering a “growth mindset”— in which intelligence is thought to be incremental and able to improve throughout life— as opposed to a “fixed mindset” can help protect against these threats that may occur as the result of differences in gender, socioeconomic status, and other sociological factors. Encourage students to take on challenges as learning and growing opportunities that will help them persist beyond obstacles and setbacks rather than think their identity makes them undeserving of success. By avoiding subtle cues to stereotype threat, we can create more positive learning environments and help our students meet academic levels they may not even know they are able to achieve.

How we can reduce situations that prime students to impose negative stereotypes onto themselves:

Place demographic surveys at the end of exams, after assessment submission

Constructive feedback that, while stating high standards, expresses that students are capable of meeting those expectations

Empowerment and self-affirmation activities: Have students copy affirmation statements at the beginning of exams or anonymously share or journal about something they were proud of. Remember that phrase you repeated at the beginning of the article now? Hopefully you enjoyed reading this article and read it at a faster, perhaps more excited pace despite all the new concepts because of this affirmation activity!

Incorporate discussion/readings about malleable intelligence and about obstacles faced by famous STEM professionals, even yourself

I recall one professor at my college who would preface each exam with the usual wishes of good luck, but also would also say, “You are all smart, amazing, wonderful students!” Just that statement would greatly reduce my testing anxiety, made me feel like I belonged in that department, and made the class overall more enjoyable to attend. Now I make sure to tell my students that before their own exams!

One difficult scenario that I often wrestled with as a Boundless Brilliance presenter was whether to admit to a classroom of students that there are less girls in STEM than boys, and that some people may not think girls are as capable in the sciences, when most or all of the class was not aware of the gender gap. I preferred to use our themes of “Everyone is brilliant” and “Anyone can be a scientist” instead of making a large point of the previous matter. While the gap is the hard, current truth, announcing (as a classroom authority) the stereotype when there is no prior conception of it in children’s minds may introduce doubt of ability, especially in the girls we are purposely aiming to encourage.

Making your classroom an equitable learning space does not have to be a complete overhaul of your pedagogy or your curriculum—progress can be as easy as checking in with their mental health halfway through the semester before midterms or asking your students how they feel about their homework. By asking ourselves, “How am I addressing privileges, implicit biases, and stereotype threat cues this month?” and performing our own self-reflections, we can identify the areas of need and encouragement for our students and ourselves with respect to our very own STEM careers. Like everything else that leads to success, practicing equity in the classroom takes practice and patience, and although it may seem difficult and frustrating at first, STEM educational advancement should involve as much collaboration as any other field; get colleagues and friends involved and share discussions, personal thoughts, and ideas with each other. Also, remember the impact you are having on each and every young mind, and how you are doing valuable work to diversify STEM fields!

Looking for more resources to empower and inspire your young scientist? Check out our workbook full of exciting science experiments and empowering activities!

Learn more and purchase today!